Few martyrs in the church are as famous as the glorious St. Lawrence, in whose praises the most illustrious among the Orthodox fathers of the West have exerted their eloquence, and whose triumph the whole church joins in a body to honor with universal joy and devotion. St. Lawrence was born in Spain of 225 AD, at Osca, a town in Aragon, near the foot of the Pyrenees. As a youth he was sent to Saragoza to complete his studies. It was there that he first encountered the future Bishop Sixtus, who was a Greek and a teacher in the most renowned center of learning at the time. Between master and disciple a communion of life and friendship grew. In time, Sixtus and Lawrence joined a migratory wave from Spain to Rome. When Sixtus was elevated to patriarch in 257, he ordained Lawrence deacon, and though Lawrence was still young, appointed him the first among the seven deacons who served in the patriarchal church; therefore he is called archdeacon of Rome. This was a position of great trust, which included the care of the treasury and riches of the church, and the distribution of alms among the poor.

Few martyrs in the church are as famous as the glorious St. Lawrence, in whose praises the most illustrious among the Orthodox fathers of the West have exerted their eloquence, and whose triumph the whole church joins in a body to honor with universal joy and devotion. St. Lawrence was born in Spain of 225 AD, at Osca, a town in Aragon, near the foot of the Pyrenees. As a youth he was sent to Saragoza to complete his studies. It was there that he first encountered the future Bishop Sixtus, who was a Greek and a teacher in the most renowned center of learning at the time. Between master and disciple a communion of life and friendship grew. In time, Sixtus and Lawrence joined a migratory wave from Spain to Rome. When Sixtus was elevated to patriarch in 257, he ordained Lawrence deacon, and though Lawrence was still young, appointed him the first among the seven deacons who served in the patriarchal church; therefore he is called archdeacon of Rome. This was a position of great trust, which included the care of the treasury and riches of the church, and the distribution of alms among the poor.The Emperor Valerian, in 257, published his edicts against the church, which he foolishly thought he was able to destroy, not knowing it to be the work of the Almighty. His hope was that by cutting off the shepherds he might disperse the flock, so he commanded all bishops, priests, and deacons to be put to death without delay. The holy patriarch Sixtus was apprehended the following year. St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, preserved an account of the death of St. Sixtus in one of his letters. Commenting on the situation of great uncertainty and unease in which the church found herself because of increasing hostility towards Christians, he notes: “The Emperor Valerian has consigned to the Senate a decree by which he has determined that all Bishops, Priests and Deacons will be immediately put to death. . . . I communicate to you that Sixtus suffered martyrdom on August 6th together with four Deacons while they were in a cemetery. The Roman authorities have established a norm according to which all Christians who have been denounced must be executed and their goods confiscated by the Imperial treasury.” The cemetery to which the holy St. Cyprian alludes is that of St. Callixtus. Sixtus was captured there while celebrating the Divine Liturgy. He was buried in the same cemetery after his martyrdom.

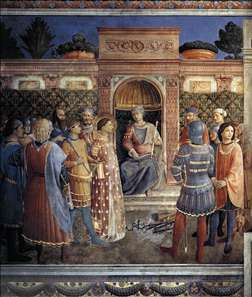

|

| Basilica of St. Lawrence |

The holy patriarch, at the sight of his grief, was moved to tenderness and compassion, and comforting him, he answered, “I do not leave you, my son. We are spared on account of our weakness and old age. But a greater trial and a more glorious victory are reserved for you, who are

stout and in the vigor of youth. You will follow me in three days.” He then commanded Lawrence immediately to distribute among the poor the treasure of the church which was committed to his care, lest the poor should be robbed of their care if it should fall into the hands of their persecutors.

Lawrence was full of joy, hearing that he should so soon be called to God, and set out immediately to seek all the poor widows and orphans, and distribute among them all the money of the church; he even sold the sacred vessels to increase the sum, employing it all in like manner. The prefect of Rome soon sent for Lawrence and said to him, “Christians often complain that we treat you with cruelty;

thought of here; I only

inquire mildly after your

charge. I am informed that

your priests offer their

divine sacrifices in vessels

of gold, that the sacred

blood is received in silver

cups, and that in your

evening services you have

candles fitted in golden

candlesticks. Bring to me

these concealed treasures;

the prince has need of them

for the maintenance of his

troops. I am told that,

according to your doctrine, you must render to Caesar the things that belong to him. I do not think that your God causes money to be coined; he brought none into the world with him; he only brought words. Give us therefore the money, and be rich in words.” Lawrence replied, without showing any concern, “The church is indeed rich, nor has the emperor any treasure equal to what it possesses. I will show you its treasures; but allow me a little time to set everything in order, and to make an inventory.” The prefect did not understand of what treasure Lawrence spoke, but imagining he possessed much hidden wealth, was satisfied with this answer and granted him three days.

During this interval, Lawrence went all over the city, seeking out in every street the poor who were supported by the church, and with whom no other was so well acquainted. On the third day he gathered together a great number of them before the church and placed them in rows, the decrepit, the blind, the lame, the maimed, the lepers, orphans, widows, and virgins; then he went to the prefect, invited him to come and see the treasure of the church, and conducted him to the place. The prefect, astonished to see such a number of poor wretches, who made a horrid sight, turned to the holy deacon with looks full of disorder and threatenings, and asked him what all this meant, and where the treasures were which he had promised to show him. Lawrence answered, “What are you displeased at? The gold that you so eagerly desire is a vile metal, and serves to incite men to all manner of crimes. The light of heaven is the true gold, which these poor objects enjoy. Their bodily weakness and sufferings are the source of their patience and virtue; vices and passions are the real diseases by which the great ones of the world are often most truly miserable and despicable. Behold in these poor persons the treasures which I promised to show you; to which I will add pearls and precious stones, those widows and consecrated virgins, which are the church’s crown, by which it is pleasing to Christ; it has no other riches; make use then of them for the advantage of Rome, of the emperor, and yourself.” In this way he exhorted him to redeem his sins by sincere repentance and almsgiving, and showed him where the church placed its treasure. However, the earthly-minded man was far from forming so noble an idea of what he saw, the sight of which offended his carnal eyes, and he cried out in a flight of rage, “Do you mock me? Is it in this way that the sacred crests of the Roman power are insulted? I know that you desire to die; that is your frenzy and vanity: but you shall not die immediately, as you imagine. I will protract your tortures, that your death may be the more bitter as it shall be slower. You shall die by inches.” Then he caused a great gridiron to be made ready and live coals to be thrown under it, that the martyr might be slowly burnt. Lawrence was stripped, stretched out, and bound with chains upon this iron bed, which broiled his flesh little by little. To the Christians watching, his face appeared to be as that of the newly baptized, surrounded with a beautiful extraordinary light, and his broiled body to emit a sweet, pleasant smell. The martyr felt none of the torments of the persecutor, so vehement was his desire of possessing Christ, and while his body broiled in the material flames, the fire of divine love, which was far more active within his breast, made him to disregard the pain. Having the law of God before his eyes, he esteemed his torments to be refreshment and a comfort. Such was the tranquility and peace of mind which he enjoyed amidst his torments that having suffered a long time, he turned to the judge and said to him, with a cheerful and smiling countenance, “Let my body be now turned; one side is broiled enough.” When, by the prefect’s order, the executioner had turned him, he said, “It is cooked enough, you may now eat.”

During this interval, Lawrence went all over the city, seeking out in every street the poor who were supported by the church, and with whom no other was so well acquainted. On the third day he gathered together a great number of them before the church and placed them in rows, the decrepit, the blind, the lame, the maimed, the lepers, orphans, widows, and virgins; then he went to the prefect, invited him to come and see the treasure of the church, and conducted him to the place. The prefect, astonished to see such a number of poor wretches, who made a horrid sight, turned to the holy deacon with looks full of disorder and threatenings, and asked him what all this meant, and where the treasures were which he had promised to show him. Lawrence answered, “What are you displeased at? The gold that you so eagerly desire is a vile metal, and serves to incite men to all manner of crimes. The light of heaven is the true gold, which these poor objects enjoy. Their bodily weakness and sufferings are the source of their patience and virtue; vices and passions are the real diseases by which the great ones of the world are often most truly miserable and despicable. Behold in these poor persons the treasures which I promised to show you; to which I will add pearls and precious stones, those widows and consecrated virgins, which are the church’s crown, by which it is pleasing to Christ; it has no other riches; make use then of them for the advantage of Rome, of the emperor, and yourself.” In this way he exhorted him to redeem his sins by sincere repentance and almsgiving, and showed him where the church placed its treasure. However, the earthly-minded man was far from forming so noble an idea of what he saw, the sight of which offended his carnal eyes, and he cried out in a flight of rage, “Do you mock me? Is it in this way that the sacred crests of the Roman power are insulted? I know that you desire to die; that is your frenzy and vanity: but you shall not die immediately, as you imagine. I will protract your tortures, that your death may be the more bitter as it shall be slower. You shall die by inches.” Then he caused a great gridiron to be made ready and live coals to be thrown under it, that the martyr might be slowly burnt. Lawrence was stripped, stretched out, and bound with chains upon this iron bed, which broiled his flesh little by little. To the Christians watching, his face appeared to be as that of the newly baptized, surrounded with a beautiful extraordinary light, and his broiled body to emit a sweet, pleasant smell. The martyr felt none of the torments of the persecutor, so vehement was his desire of possessing Christ, and while his body broiled in the material flames, the fire of divine love, which was far more active within his breast, made him to disregard the pain. Having the law of God before his eyes, he esteemed his torments to be refreshment and a comfort. Such was the tranquility and peace of mind which he enjoyed amidst his torments that having suffered a long time, he turned to the judge and said to him, with a cheerful and smiling countenance, “Let my body be now turned; one side is broiled enough.” When, by the prefect’s order, the executioner had turned him, he said, “It is cooked enough, you may now eat.”

During this interval, Lawrence went all over the city, seeking out in every street the poor who were supported by the church, and with whom no other was so well acquainted. On the third day he gathered together a great number of them before the church and placed them in rows, the decrepit, the blind, the lame, the maimed, the lepers, orphans, widows, and virgins; then he went to the prefect, invited him to come and see the treasure of the church, and conducted him to the place. The prefect, astonished to see such a number of poor wretches, who made a horrid sight, turned to the holy deacon with looks full of disorder and threatenings, and asked him what all this meant, and where the treasures were which he had promised to show him. Lawrence answered, “What are you displeased at? The gold that you so eagerly desire is a vile metal, and serves to incite men to all manner of crimes. The light of heaven is the true gold, which these poor objects enjoy. Their bodily weakness and sufferings are the source of their patience and virtue; vices and passions are the real diseases by which the great ones of the world are often most truly miserable and despicable. Behold in these poor persons the treasures which I promised to show you; to which I will add pearls and precious stones, those widows and consecrated virgins, which are the church’s crown, by which it is pleasing to Christ; it has no other riches; make use then of them for the advantage of Rome, of the emperor, and yourself.” In this way he exhorted him to redeem his sins by sincere repentance and almsgiving, and showed him where the church placed its treasure. However, the earthly-minded man was far from forming so noble an idea of what he saw, the sight of which offended his carnal eyes, and he cried out in a flight of rage, “Do you mock me? Is it in this way that the sacred crests of the Roman power are insulted? I know that you desire to die; that is your frenzy and vanity: but you shall not die immediately, as you imagine. I will protract your tortures, that your death may be the more bitter as it shall be slower. You shall die by inches.” Then he caused a great gridiron to be made ready and live coals to be thrown under it, that the martyr might be slowly burnt. Lawrence was stripped, stretched out, and bound with chains upon this iron bed, which broiled his flesh little by little. To the Christians watching, his face appeared to be as that of the newly baptized, surrounded with a beautiful extraordinary light, and his broiled body to emit a sweet, pleasant smell. The martyr felt none of the torments of the persecutor, so vehement was his desire of possessing Christ, and while his body broiled in the material flames, the fire of divine love, which was far more active within his breast, made him to disregard the pain. Having the law of God before his eyes, he esteemed his torments to be refreshment and a comfort. Such was the tranquility and peace of mind which he enjoyed amidst his torments that having suffered a long time, he turned to the judge and said to him, with a cheerful and smiling countenance, “Let my body be now turned; one side is broiled enough.” When, by the prefect’s order, the executioner had turned him, he said, “It is cooked enough, you may now eat.”

During this interval, Lawrence went all over the city, seeking out in every street the poor who were supported by the church, and with whom no other was so well acquainted. On the third day he gathered together a great number of them before the church and placed them in rows, the decrepit, the blind, the lame, the maimed, the lepers, orphans, widows, and virgins; then he went to the prefect, invited him to come and see the treasure of the church, and conducted him to the place. The prefect, astonished to see such a number of poor wretches, who made a horrid sight, turned to the holy deacon with looks full of disorder and threatenings, and asked him what all this meant, and where the treasures were which he had promised to show him. Lawrence answered, “What are you displeased at? The gold that you so eagerly desire is a vile metal, and serves to incite men to all manner of crimes. The light of heaven is the true gold, which these poor objects enjoy. Their bodily weakness and sufferings are the source of their patience and virtue; vices and passions are the real diseases by which the great ones of the world are often most truly miserable and despicable. Behold in these poor persons the treasures which I promised to show you; to which I will add pearls and precious stones, those widows and consecrated virgins, which are the church’s crown, by which it is pleasing to Christ; it has no other riches; make use then of them for the advantage of Rome, of the emperor, and yourself.” In this way he exhorted him to redeem his sins by sincere repentance and almsgiving, and showed him where the church placed its treasure. However, the earthly-minded man was far from forming so noble an idea of what he saw, the sight of which offended his carnal eyes, and he cried out in a flight of rage, “Do you mock me? Is it in this way that the sacred crests of the Roman power are insulted? I know that you desire to die; that is your frenzy and vanity: but you shall not die immediately, as you imagine. I will protract your tortures, that your death may be the more bitter as it shall be slower. You shall die by inches.” Then he caused a great gridiron to be made ready and live coals to be thrown under it, that the martyr might be slowly burnt. Lawrence was stripped, stretched out, and bound with chains upon this iron bed, which broiled his flesh little by little. To the Christians watching, his face appeared to be as that of the newly baptized, surrounded with a beautiful extraordinary light, and his broiled body to emit a sweet, pleasant smell. The martyr felt none of the torments of the persecutor, so vehement was his desire of possessing Christ, and while his body broiled in the material flames, the fire of divine love, which was far more active within his breast, made him to disregard the pain. Having the law of God before his eyes, he esteemed his torments to be refreshment and a comfort. Such was the tranquility and peace of mind which he enjoyed amidst his torments that having suffered a long time, he turned to the judge and said to him, with a cheerful and smiling countenance, “Let my body be now turned; one side is broiled enough.” When, by the prefect’s order, the executioner had turned him, he said, “It is cooked enough, you may now eat.” The prefect insulted him in return, but the martyr continued in earnest prayer, with sighs and tears imploring the divine mercy with his last breath for the conversion of the ungodly. The saint having finished his prayer, and completed his holy offering, lifting up his eyes towards heaven, he gave up his spirit. Several senators who were present at his death were so powerfully moved by his tender and heroic fortitude and piety that they became Christians upon the spot. These noblemen took up the martyr’s body on their shoulders and gave it an honorable burial in the Veran field, near the road to Tibur, on the 10th of August, in 258. It is known that he was buried in the cemetery of Cyriaca in agro Verano on the Via Tiburtina. St. Lawrence’s death was the death of idolatry in Rome, which, from that time, began more significantly to decline. From the moment of his burial, the faithful venerate his tomb with great devotion and fervor, commending themselves in all their needs to his patronage. An incredible number of miracles have been worked through the intercession of St. Lawrence. From the third century, the feast of St. Lawrence has been kept faithfully. Within fifty years of his martyrdom, the Christian emperor Constantine had a patriarchal church built over his tomb, on the road to Tibur; one of five churches where the patriarch of Rome celebrated regularly, the site now known as the church of St. Lawrence-outside-the-Walls. By the fifth century, the church had established his feast with a vigil, a weeklong after-feast and leave-taking. By the sixth century, the feast of St. Lawrence was one of the most celebrated Orthodox feasts throughout Western Europe. For centuries the Perseid meteor shower coinciding with his feast has been referred to as the ‘Tears of St. Lawrence.” The holy martyrdom of St. Lawrence and the power of his intercession on our behalf is hailed and testified to in the writings of St. Gregory of Tours, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Leo, St. Fulgentius, St. Optatus, Eusebius, and the fourth-century Orthodox poet Prudentius. The San Lorenzo Valley (Santa Cruz County, California) received the name of this great Orthodox saint from the Portola Expedition on October 17, 1769. St. Lawrence Orthodox Church, Felton, California, celebrates his feast on the Sunday nearest August 10 (Old Calendar).

The prefect insulted him in return, but the martyr continued in earnest prayer, with sighs and tears imploring the divine mercy with his last breath for the conversion of the ungodly. The saint having finished his prayer, and completed his holy offering, lifting up his eyes towards heaven, he gave up his spirit. Several senators who were present at his death were so powerfully moved by his tender and heroic fortitude and piety that they became Christians upon the spot. These noblemen took up the martyr’s body on their shoulders and gave it an honorable burial in the Veran field, near the road to Tibur, on the 10th of August, in 258. It is known that he was buried in the cemetery of Cyriaca in agro Verano on the Via Tiburtina. St. Lawrence’s death was the death of idolatry in Rome, which, from that time, began more significantly to decline. From the moment of his burial, the faithful venerate his tomb with great devotion and fervor, commending themselves in all their needs to his patronage. An incredible number of miracles have been worked through the intercession of St. Lawrence. From the third century, the feast of St. Lawrence has been kept faithfully. Within fifty years of his martyrdom, the Christian emperor Constantine had a patriarchal church built over his tomb, on the road to Tibur; one of five churches where the patriarch of Rome celebrated regularly, the site now known as the church of St. Lawrence-outside-the-Walls. By the fifth century, the church had established his feast with a vigil, a weeklong after-feast and leave-taking. By the sixth century, the feast of St. Lawrence was one of the most celebrated Orthodox feasts throughout Western Europe. For centuries the Perseid meteor shower coinciding with his feast has been referred to as the ‘Tears of St. Lawrence.” The holy martyrdom of St. Lawrence and the power of his intercession on our behalf is hailed and testified to in the writings of St. Gregory of Tours, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Leo, St. Fulgentius, St. Optatus, Eusebius, and the fourth-century Orthodox poet Prudentius. The San Lorenzo Valley (Santa Cruz County, California) received the name of this great Orthodox saint from the Portola Expedition on October 17, 1769. St. Lawrence Orthodox Church, Felton, California, celebrates his feast on the Sunday nearest August 10 (Old Calendar).Prayer to our Patron Saint

O saint of God, Lawrence, deacon martyr, pray to God for me, for my home and my family. --Amen.

Pray to God for me, O Saint Lawrence, well-pleasing to God, for I readily recommend myself to you, who are the speedy helper and intercessor for my soul. --Amen.

Early on, the life and miracles of St. Lawrence were collected in a work titled, The Acts of St. Lawrence, which is now lost. The earliest existing documentation of miracles associated with St. Lawrence is found in the writings of St. Gregory of Tours (538–594). Miracles that occurred during St. Gregory’s lifetime include: “A priest named Fr. Sanctulus was rebuilding a church of St. Lawrence, which had been attacked and burnt, and hired many workmen to accomplish the job. At one point during the construction, he found himself with nothing to feed them. He prayed to St. Lawrence for help, and looking in his basket he found a fresh, white loaf of bread, it seemed to him too small to feed the workmen, but in faith he began to serve it to the men. While he broke the bread, it so multiplied that that his workmen fed from it for ten days. “Once a certain priest was repairing the church of St. Lawrence, and one of the essential beams was found to be too short for its span, therefore the priest prayed to St. Lawrence asking that the saint who had seen to the well-being of the poor would help him in his poverty of good lumber. And the beam grew in length so suddenly and significantly that it had to be cut for it was too long. The priest took the remainder, parted it into many pieces which he distributed among the faithful and by venerating the wood many were healed.” The holy Bishop Fortunatus of Poitiers (530–600), a contemporary of St. Gregory, a poet and the hymnographer who wrote the services for St. Martin of Tours, witnessed a man suffering greatly with a toothache who only touched this wood and was instantly healed.

On the Feast of St. Lawrence

by St. Leo the Great, Patriarch of Rome

On the 10th of August celebrate the Feast Day of St. Lawrence. While the height of all virtues, dearly-beloved, and the fullness of all righteousness is born of that love by which God and one’s neighbor is loved, surely in none is this love found more conspicuous and brighter than in the blessed martyrs; they who are near to our Lord Jesus, who died for all men, by the imitation of His love in their suffering. For although that Love, by which the Lord has redeemed us, cannot be equaled by the effort of any man (because it is one thing that a man who is doomed to die one day should die for a righteous man, and another that One who is free from the debt of sin should lay down His life for the wicked), yet the martyrs also have done great service to all men, in that the Lord who gave them boldness, has used it to show that the penalty of death and the pain of the Cross need not be terrible to any of His followers, but might be imitated by many of them. No model is more useful in teaching God’s people than that of the martyrs. Eloquence may make intercession easy, reasoning may effectually persuade; but examples are stronger than words, and there is more teaching in practice than in precept. And how gloriously strong in this most excellent manner of doctrine that the blessed martyr Lawrence is, whose memory we commemorate today. Even his persecutors were able to feel his faith, when they found that his wondrous courage, born principally of love for Christ, not only did not yield itself, but also strengthened others by the example of his endurance. For when the fury of the gentile rulers was raging against Christ’s most chosen members, and attacked those especially who were of priestly rank, the wicked persecutor’s wrath was vented on Lawrence the deacon, who was preeminent not only in the performance of the sacred rites, but also in the management of the church’s property, promising himself double spoil from one man’s capture: for if he forced him to surrender the sacred treasures, he would also drive him out of his true religion. And so this man, so greedy of money and such a foe to the truth, arms himself with a double weapon: with avarice to plunder the gold, and with impiety to capture Christ.

|

| St. Leo the Great, Patriarch of Rome |

St. Laurence and The Holy Grail

Lawrence was born in Huesca, Spain which is located in what is now known as Northern Aragon. Lawrence spent most of his life in Huesca and recieved religious guidance from local priests and deacons. Until he was brought to Rome by Pope Sixtus II, who at the time was the Archdeacon of Rome. When Sixtus was ordained Bishop of Rome, Pope, Lawrence was ordained a deacon in 257. Sixtus then stationed him as the first Archivist of the Catholic Church.And under his job he had to take care of the holiest chalice known to Christians everywhere, he was given the Holy Grail so he could keep it far away for the Persecution of Christians under Valerian was starting to heat up. Lawrence sent the Chalice away to Huesca with a letter to his parents to give it to a Monk who was a friend of Lawrence and the family. The Chalice was taken to the monastery where it remained hidden for centuries, and many believe that the Chalice is now in the Cathedral of Valencia.

In the persecutions under Valerian in 258 A.D., numerous priests and deacons were put to death, while Christians belonging to the nobility or the Roman Senate were deprived of their goods and exiled. Pope Sixtus II was one of the first victims of this persecution, being beheaded on August 6. A legend cited by St Ambrose of Milan says that Lawrence met the Pope on his way to his execution, where he is reported to have said, "Where are you going, my dear father, without your son? Where are you hurrying off to, holy priest, without your deacon? Before you never mounted the altar of sacrifice without your servant, and now you wish to do it without me?" The Pope is reported to have prophesied that "after three days you will follow me".

After the death of Sixtus, the prefect of Rome demanded that Lawrence turn over the riches of the Church. Ambrose is the earliest source for the tale that Lawrence asked for three days to gather together the wealth. Lawrence worked swiftly to distribute as much Church property to the poor as possible, so as to prevent its being seized by the prefect. On the third day, at the head of a small delegation, he presented himself to the prefect, and when ordered to give up the treasures of the Church, he presented the poor, the crippled, the blind and the suffering, and said that these were the true treasures of the Church. One account records him declaring to the prefect, "The Church is truly rich, far richer than your emperor." This act of defiance led directly to his martyrdom. Lawrence is said to have been martyred on a gridiron as a part of Valerian's persecution. During his torture Lawrence cried out "This side’s done, turn me over and have a bite."

The Valencia Chalice

The other surviving Holy Chalice vessel is the santo cáliz, an agate cup in the Cathedral of Valencia. It is preserved in a chapel consecrated to it, where it still attracts the faithful on pilgrimage.The piece is a hemispherical cup made of dark red agate which is mounted by means of a knobbed stem and two curved handles onto a base made from an inverted cup of chalcedony. The agate cup is about 9 centimeters/ 3.5 inches in diameter and the total height, including base, is about 17 centimeters/ 7 inches high. The agate cup, without the base, fits a description by Saint Jerome. The lower part has Arabic inscriptions.

After an inspection in 1960, the Spanish archaeologist Antonio Beltrán asserted that the cup was produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century BC and the 1st century AD. The surface has not been dated by microscopic scanning to assess recrystallization.

The first explicit inventory reference to the present Chalice of Valencia dates from 1134, an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up by Don Carreras Ramírez, Canon of Zaragoza, December 14, 1134: "En un arca de marfil está el Cáliz en que Cristo N. Señor consagró su sangre, el cual envió S. Lorenzo a su patria, Huesca". According to the wording of this document, the Chalice is described as the vessel in which "Christ Our Lord consecrated his blood".

Reference to the chalice is made in 1399, when it was given by the monastery of San Juan de la Peña to king Martin I of Aragon in exchange for a gold cup. By the end of the century a provenance for the chalice can be detected, by which Saint Peter had brought it to Rome.

Pope John Paul II himself celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982, causing some uproar both in skeptic circles and in the circles that hoped he would say accipiens et hunc praeclarum Calicem ("this most famous chalice") in lieu of the ordinary words of the Mass taken from Matthew 26:27). For some people, the authenticity of the Chalice of Valencia failed to receive papal blessing.

In Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail, Janice Bennett gives an account of the chalice's history, carried on Saint Peter's journey to Rome, entrusted by Pope Sixtus II to Saint Lawrence in the third century, sent to Huesca in Spain when the Hispanic saint was martyred on a gridiron during the Valerian persecution in Rome in AD 258, sent to the Pyrenees for safekeeping, where it passed from monastery to monastery, in accordance with all the claims to former possession of the Chalice, and venerated by the monks of the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña. Emerging there into the light of history, the monastery's agate cup was acquired by King Martin I of Aragon in 1399 who kept it at Zaragoza. After his death, King Alfonso V of Aragón brought it to Valencia, where it has remained.

Bennett presents as historical evidence a 6th-century manuscript Latin Vita written by Donato, an Augustinian monk who founded a monastery in the area of Valencia, which contains circumstantial details of the life of Saint Laurence and details surrounding the transfer of the Chalice to Spain. The original manuscript does not exist, but a 17th-century Spanish translation entitled "Life and Martyrdom of the Glorious Spaniard St. Laurence" is in a monastery in Valencia. The main source for the life of St. Laurence, the poem Peristephanon by the 5th-century poet Prudentius, does not mention the Chalice that was later said to have passed through his hands.

In 1960 the Spanish archeologist Antonio Beltrán studied the Chalice and concluded: "Archeology supports and definitively confirms the historical authenticity". "Everyone in Spain believes it is the cup," Bennett said to a reporter from the Denver Catholic Register. "You can see it every day that the chapel is open."