|

| Godfrey of Bouillon and leaders of the first crusade |

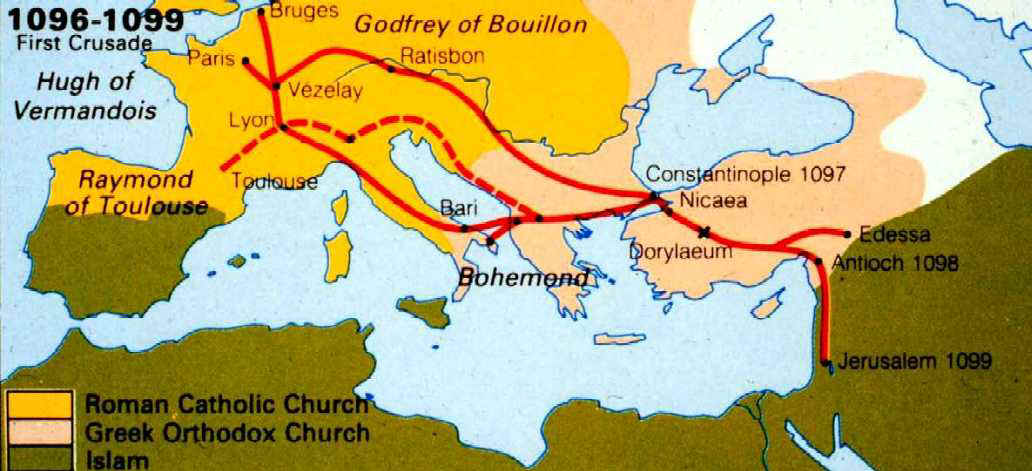

The first crusade marks a major turning point in the history of Europe, marking the first major war of conquest launched from western Europe since the decline of the Roman Empire. The period immediately before the crusade saw the rise of the Seljuk empire. 1071 saw both the defeat of Byzantium at Manzikert, and their conquest of Jerusalem, which made pilgrimage much more dangerous - previously the pilgrim remaining in Christian lands almost until reaching the Holy Land, but the loss of Anatolia to the Turks made the journey far more dangerous, while tales of attacks on pilgrims circulated throughout Europe. Thus when the Emperor Alexius Comnenus made an appeal for aid from western Europe, there was an audience ready to respond to Pope Urban II's call to arms at the Synod of Clermont (1095). The resulting enthusiasm had several results, including the People's Crusade, and a series of anti-Jewish atrocities committed in Germany, but the main crusade was better organised. However, there was never a proper command structure, in part because the crusade attracted a series of important leaders, but no crowned monarchs, who could have assumed overall control.

|

| The First Crusade |

The principal leaders were the Normans Duke Bohemund of Taranto, his nephew Tancred, and Duke Robert of Normandy, along with Count Reymond of Toulouse, Duke Godfrey de Bouillon of Lorraine, his brother Baldwin, Duke Hugh of Vermandois, brother of the king of France, Count Stephan of Blois, and Count Robert of Flanders. From the start there were tensions between these leaders, but at least until his death, the Papal legate, Bishop Adhemar de Puy, was able to keep these tensions from causing too many problems. The various groups agreed to assemble at Constantinople, and each group travelled separately, some travelling along the Danube, others down the Dalmatian coast, and still more down Italy and then by sea to Greece. The assembly at Constantinople was troublesome - Alexius had not expected an army of 50,000 enthusiasts, having probably hoped for a few thousand mercenaries, and over the winter of 1096-7 the two sides bickered. Alexius wanted to re-conquer Anatolia, lost after 1071, but that was of little interest to the crusaders, but eventually they came to an agreement, with Alexius agreeing to aid their march to the Holy Land, while the crusaders agreed that any lands they conquered would be held from the Byzantine Empire, a promise they probably never intended to honour.

|

| Battle Field |

Finally, in the spring of 1097 the crusaders finally came to grips with the Moslems. Despite their lack of interest in the re-conquest of Anatolia, the crusaders still had to cross it, and the Turks controlled most of the area. The first target for the crusaders was Nicaea, dangerously close to Constantinople. The siege of Nicaea lasted from 14 May-19 June 1097, and just when the crusaders were about to break into and sack the city, Alexius negotiated its surrender and managed to get troops into the city, once again souring relations between the Byzantines and the crusaders. The crusaders now began their march across Anatolia, marching in two parallel columns, with no overall command. At the battle of Dorylaeum (1 July 1097), Bohemund's column was nearly annihilated by a much larger Turkish force, and was only saved by the arrive of Godfrey and Reymond from the other column. Soon after, the first contingent left the army, when Baldwin left to carve out his own principality centred on Edessa. Meanwhile the main crusader army reached Antioch. The resulting siege of Antiioch lasted from 21 October 1097 to 3 June 1098. Once again, the crusade came close to disaster, this time from starvation, and were only saved by late arriving English and Pisan fleets, before finally capturing the city with the aid of a Turkish traitor on 3 June, only two days before a 75,000 strong Turkish army arrived, trapping the crusaders inside the city, where they were themselves besieged from 5-28 June. The siege was ended on 28 June, when the massively outnumbered crusaders sallied from the city, with at most 15,000 combatants. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the crusaders won the resulting battle of the Orontes (28 June 1098). At this point disaster stuck, with the death of Bishop Adhemar, after which tensions between the leaders grew worse. When the crusaders moved on to march against Jerusalem, Bohemund and the Normans remained in Antioch, where they founded their own principality.

|

| Holy War |

The remaining crusaders now found themselves facing a new foe, the Fatimids, who had re-conquered Jerusalem. The remaining 12,000 crusaders reached Jerusalem in far too weak a condition to maintain a siege similar to that at Antioch, and the siege of Jerusalem (9 June-18 July 1099) was dominated by preparation for the successful assault, which defeated the more numerous Fatimid defenders. After the fall of the city, the crusades sacked the city, massacring much of the population, not limiting themselves to the Moslems, shocking even their contemporaries with the violence of the sack. Godrey of Bouillon was now elected Guardian of Jerusalem, but faced one more threat, when a Fatamid relieving army arrived from Egypt. Despite outnumbering the Crusaders 5 to 1, the Fatamid army was nowhere near as dangerous as the Turks had been, and Godrey won a crushing victory at the Battle of Ascalon (12 August 1099). The crusade had been an overwhelming success, but the seeds of eventual failure were already present. The crusaders established four principalities - Jerusalem, Edessa, Tripoli and Antioch - which were often at odds with each other, while many of the crusaders returned home soon after their victory, reducing the crusader strength in the east. Despite that, the crusader kingdoms managed to survive until the fall of Acre in 1291.